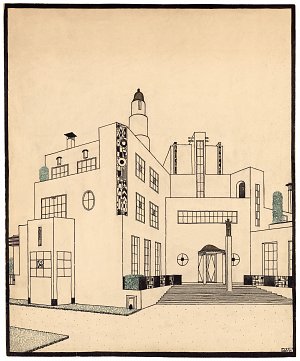

Robert Mallet-Stevens (1886-1945) : Project for a country house for Jacques Doucet, circa 1924

Robert Mallet-Stevens (1886-1945), Project for a country house for Jacques Doucet, circa 1924

Ink on Bristol board, 56.7 x 46.7 cm, inv. 38603 A13

© ADAGP, Paris / Photo MAD, Paris

In 1924, the couturier and collector Jacques Doucet commissioned Robert Mallet-Stevens to design a house at Marly that was never built. This drawing was also intended to be exhibited, published and impress future clients, just as his book “A Modern City” had done in 1922. The whiteness of the paper accentuates the characteristically bare walls of the modern movement. At the same time, Mallet-Stevens was positioning himself as heir to the Viennese Secession with his juxtaposition of volumes, vertical windows, ornate decoration, stained glass, wrought ironwork and antique statuary (all features of the Stoclet Palace, the mansion designed by Jules Hoffman for one of Mallet-Stevens’ uncles). The drawing also shows the influence of De Stijl, the Dutch movement that prompted Mallet-Stevens towards asymmetry in his arrangement of volumes. The perspective view, the lines drawn freehand with unvarying thickness, the walls devoid of texture, the windows left white instead of the usual black, and the abstractness of the vegetation (the only touch of colour in the drawing) highlight the Cubist values of this architecture of volumes.

Filippo Juvarra (1678-1736) : Initial project for the Chapel of Saint Hubert, Venaria Reale, Turin, circa 1716

Filippo Juvarra (1678-1736), Initial project for the Chapel of Saint Hubert, Venaria Reale, Turin, circa 1716

Pen and brown ink, 15.9 x 31.3 cm, inv. CD 73

© MAD, Paris

Commissioned by Victor Amadeus II of savoy, the Chapel of Saint Hubert in the Venaria Reale near Turin was built by Filippo Juvarra between 1716 and 1729. This drawing is a perfect example of a sketch in which the architect tests his ideas on paper. Juvarra’s aim here was to judge the effect of the chapel’s silhouette against its surroundings of the large forecourt in the foreground, the end of a wing of the palace on the right, and a vast park and the Piedmont mountains beyond. Having initially envisaged a façade with a colossal order without a dome and framed by two towers Juvarra opted for a Roman-style elevation with two levels surmounted by a high tambour and a slender dome. The dome was never realized and its lantern would have been taller than the palace itself. Two exedras link the porticos to the main body of the chapel and give the architectural composition its dynamic spatial depth. Juvarra’s pen deposited the brown ink with precision, suggesting clouds, figures and shadows with subtle hatching. Having trained as an engraver at Messina in Sicily, he had an acute sense of detail and legibility, drawing rapidly freehand and concentrating on conveying the masses, distances and the relationships between each element. This sketch perfectly illustrates this preliminary stage in architectural creation.

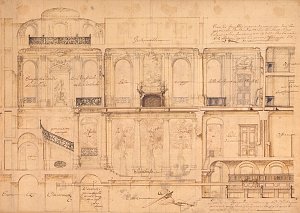

Gilles-Marie Oppenord (1672-1742) : Project for the house of Pierre-Nicolas Gaudion, circa 1732

Gilles-Marie Oppenord (1672-1742), Project for the house of Pierre-Nicolas Gaudion, circa 1732

Black ink, iron gall ink, ink wash on rag paper, 131 x 152 cm, inv. 19128

© MAD, Paris

Son of one of the king’s cabinetmakers, Oppenord trained for seven years in Italy before returning to Paris to work as an architect for the church and embarking on a successful career as an illustrator. From 1713, he worked for the Duke or Orléans on the Palais, Royal, the Château de Saint-Cloud and the Eglise Saint-Sulpice. He was ennobled in 1722 but lost his illustrious patron the following year and turned to Parisian financiers for commissions. One such client was Pierre-Nicolas Gaudion, treasurer of the French Navy, for whom Oppenord built a mansion in the Marais in 1732. The Musée des Arts Décoratifs has a number of drawings made for its construction, acquired from Paul Blondel in 1913. In this section of the staircase and dining room, the Indian ink highlights the dark wrought ironwork and Oppenord makes full use of engraving techniques such as crosshatched shading. The graphite decoration is conceived as an integral part of the architecture and he introduces the effect of transparency by including a view of the garden beyond. In this superb image, at once a presentation drawing for the client a repeatedly altered working drawing and a plan for the builders on site, the architect shows his extraordinary technical mastery and very free yet perfectly controlled drawing.

Louis-Pierre Baltard (1764-1846) : Interior view of the Eglise Saint-Sauveur, circa 1783

Louis-Pierre Baltard (1764-1846), Interior view of the Eglise Saint-Sauveur, circa 1783

Pen and Indian ink, wash, watercolour and gouache heightening, 43 x 36.5 cm, inv. PE 372

© MAD, Paris

The Eglise Saint-Sauveur, a 13th-century church in Paris’ financial district rebuilt during the Renaissance, was in semi-ruin by the end of the century of the Enlightenment. The architect Bernard Poyet, controller of buildings for the City of Paris, was chosen in 1784 to entirely rebuild it, but construction work ceased in 1791 and never resumed. Poyet designed an antique-style church with its nave separated from the side aisles by ten Corinthian columns supporting a continuous entablature and a barrel vault with caissons imitating those of the Pantheon in Rome. The choir is a wide, semi-circular apse with its central altar lit by an oculus concealed from the congregation. Louis-Pierre Baltard, future architect of the Lyon Law Courts, was then a pupil at the Académie d’Architecture, where he had proven his talents as a draughtsman. Poyet probably commissioned this picture to celebrate his project. By exaggerating contrasts of light and dark, accentuating the perspective and steeping the church interior in atmospheric effects, Baltard espoused the aesthetic of the sublime that was championed by disciples of Piranesi such as Desprez, De Wailly and Boullée and was part of the growing trend of primitivism in religious architecture.

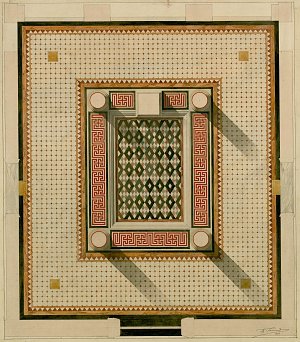

Alfred-Nicolas Normand (1822-1909) : Pompeian house, floor of the atrium, 1861

Alfred-Nicolas Normand, Pompeian house, floor of the atrium, 1861

Graphite, pen and black ink, watercolour, gouache, 56 x 48.5 cm, inv. CD 2808.14

© MAD, Paris

The house built on avenue Montaigne in 1860 for Prince Napoleon, youngest son of King Jerome of Westphalia, was intended to be place for festivities and receptions and a Parisian retreat dedicated to theatre, music, the arts and literature. It represents the height of the Pompeian vogue in France. With the tragedian actress Rachel, Théophile Gautier, Gérôme and Ingres as his protégés, Prince Napoleon commissioned the architect Normand, author of an acclaimed study of the House of the Faun in Pompeii, to design this residence. Almost all the drawings for the design and construction were donated to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs by Paul Normand, the architect’s son. This drawing of the floor of the atrium, the inner courtyard at the heart of the Greaco-Roman house, illustrated the modernity of ancient architecture revitalized by colour advocated by the generation led by Labrouste and Hittorff that soon became known as the “Neo-Greeks”. Normand’s extraordinarily beautiful presentation drawings are a manifesto for this new architecture, which was to last less than a generation. The Pompeian House was demolished in 1891.

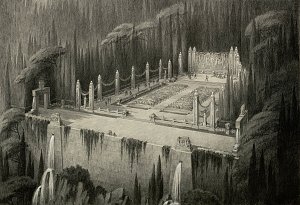

Achille Duchêne (1866-1947) et Brabant : Dream Garden: Interior of an Icelandic crater, theatre of greenery, after 1935

Achille Duchêne (1866-1947) and Brabant, Dream Garden, Interior of an Icelandic crater, theatre of greenery, after 1935

Black pencil, white heightening, 41.9 x 59.5 cm, inv. CD 3027.84

© MAD, Paris

Son of the gardener Henri Duchêne, Achille Duchêne – “the prince of gardens as he became known – was the greatest landscape gardener of the Belle Époque. A great admirer of Le Nôtre, he remodeled the classical gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte, Courances and Bleinheim Palace and designed urban gardens for European and Anglo-Saxon high-society. His wife donated a major collection of his presentation drawings to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs executed by his draughtsman, Brabant, who usually used black pencil heightened with white to accentuate contrast and perspective effects. In the 1930s, as commissions grew rarer, Duchêne turned to publishing and produced an album “Les Jardins de l’avenir” in 1935. This drawing, intended to be part of the Dream Gardens series, shows Duchêne’s rich imagination and penchant for the marvelous, a far cry from the severity so often associated with the French-style garden.