The subject of this exhibition arose from the study of one particular shoe within the museum’s collection, which belonged to Marie-Antoinette in 1792. Measuring just twenty-one centimetres in length and five centimetres in width, it seemed implausible that a thirty-seven-year old woman could have slipped her foot into such a tiny shoe. Research revealed that aristocratic women in the 18th century, and women of the haute bourgeoisie in the 19th century actually walked very little their restricted mobility was such that their shoes were in effect, not made for walking.

Shoe belonging to Marie-Antoinette, 1792

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs

© MAD Paris / photo: Christophe Dellière

How have women who subscribed to the cult of the small foot – either in Europe since the seventeenth century (Charles Perrault wrote Cinderella in 1697), or in China since the eleventh century – reconciled the idea that beauty and practicality could be one in the same? Over time, what technical characteristics have

brought greater comfort to footwear in general?

Women’s sandal, c. 1942

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs

© MAD Paris / photo: Hughes Dubois

The exhibition opens with an analysis of how we walk in our daily lives, from childhood to adulthood, in Europe, Africa, Asia and America. From the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, we can trace how certain environmental factors, such as irregular or muddy ground, constrain people’s ability to walk, requiring the use of specially adapted shoes. In France under the Occupation, scarce resources resulted in the use of wooden soles that made the wearer’s step halting and noisy. The diversity of forms that shoes can take is surveyed through a study of pieces with flat soles, high heels and platform heels, each of which has a direct impact on the comfort of the shoe.

The cults of small, bound feet in China and constrained feet in seventeenth- and

eighteenth-century France are revealed through photographs, mouldings, caricatures and shoes.” A designated “fitting room” space punctuates the exhibition’s circuit with an opportunity for visitors to actively participate: children and adults alike can try walking around in one of eight extraordinary shoe models recreated identically by shoemaker Fred Rolland.

The exhibition also looks at footwear for activities such as sport, dance, and military marching. Clown shoes and footwear belonging to Charlie Chaplin are displayed alongside with “magical” shoes, such as the Greek god Hermes’ winged sandals or the folkloric seven-league boots.

Shoe fetishism, represented by the inclusion of elegant leather shoes with

vertiginous heels and ultra-high laceup boots, influenced the fantasies of

bourgeois nineteenth-century society. Closer to our time, shoes and photographs

from 2007 recall the collaboration between Christian Louboutin and David Lynch: the famous shoemaker asked the director to photograph the dancers from the Crazy Horse wearing shoes with exaggerated high heels in a deliberately fetishist context.

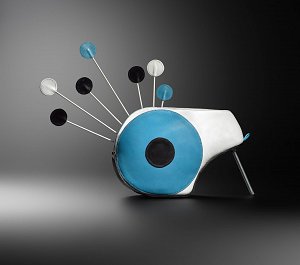

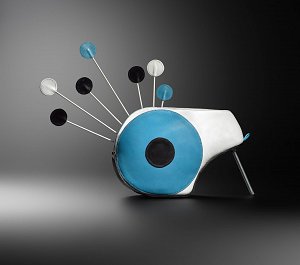

Benoit Méléard, Hommage à Calder shoe, “O” collection 1999

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs

© MAD, Paris / photo: Hughes Dubois

The exhibition closes with a selection of contemporary shoes with dramatic, extreme designs in which it is difficult, if not impossible, to walk. What motivates designers such as Benoît Méléard, Noritaka Tatehana, Masaya Kushino, Alexander McQueen and Iris van Herpen – more artists than traditional shoemakers – to push the boundaries of functionality and render the wearer immobile?

Benoit Méléard, Hommage à Calder shoe, “O” collection 1999

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs

© MAD, Paris / photo: Hughes Dubois

Marche et démarche casts a new and surprising light on an everyday item that we thought we knew.