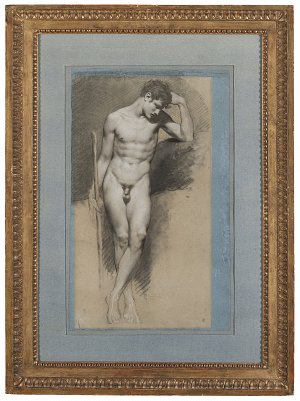

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon, Nude young man, 1st quarter of the 19th century

Donation in memory

of Mr. Émile Perrin, member of the Institut, by his son Émile, 1909

© MAD, Paris / Photograph: Jean Tholance

The Cabinet of Drawings was created in 1974 by François Mathey, then Chief Curator of the Museum, at the suggestion of Marie-Noël de Gary. The collection itself was started in the 1880s, shortly after the institution was founded, with legendary donations by eminent art lovers such as Jules Maclet, whose utopian project was to author a pictorial encyclopedia, and Philippe de Chennevières, one of the most famous collectors of his era. Judicious acquisitions from public auctions (1885, 1891, 1896) completed these generous donations: for instance, rare drawings of furniture by André Charles Boulle, that survived a fire that destroyed his workshop in 1720.

Auguste Rodin, Centaur and Child, C. 1890

Auguste Rodin Donation, 1908

© MAD, Paris

Artists and their descendants also contributed to the Cabinet with major donations. Auguste Rodin gave eight of his drawings in 1908. Jean Dubuffet, Jean Royère and Emilio Terry offered the Museum complete ensembles drawn from their studios, shedding light on their creative process and revealing the more intimate side of their work. Over the past 150 years, the Museum has assembled an exceptional collection featuring the greatest masters and creators. These unique pieces are presented alongside decorative series – one of the hallmarks of the museum – such as projects for Art Nouveau wallpaper, katagami (Japanese stencils), Art Deco jewels, and more.

Displayed on level 3, the exhibition, presented like an alphabet book, was designed to evoke a mysterious world behind the scenes: the museum’s storerooms. For instance, works may be shown in their transport cases. The circuit leads to the permanent galleries and ends in the Library.

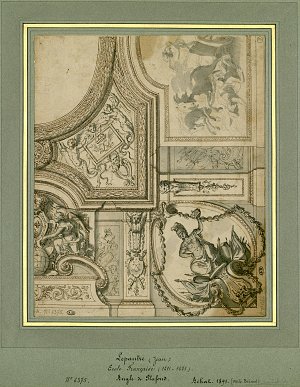

Charles Le Brun, Project for the ceiling of the Grand Cabinet du roi in the Tuileries, c. 1665-1671

Acquisition, 1891

© MAD, Paris

The display begins with A for Architecture. Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau’s sketchbook of views of antique monuments, a priceless Renaissance document, is displayed alongside Robert Mallet-Stevens’ iconic “Pavilion of Tourism” for the exhibition of 1925, and the dream-like compositions of Emilio Terry. If architecture leads the way, its corollary, D for Decor, is just as richly represented, with studies for ceilings by Charles Le Brun and Charles de La Fosse, recently attributed and therefore shown for the first time to the public, as well as works by Claude III Audran. E for Ensemblist follows with Percier and Fontaine’s Recueil des decorations intérieures and projects conceived by major interior designers such as Francis Jourdan, Robert Mallet-Stevens and Pierre Chareau, whose study-library of the French Embassy Pavilion for the exhibition of 1925 is displayed in the museum.

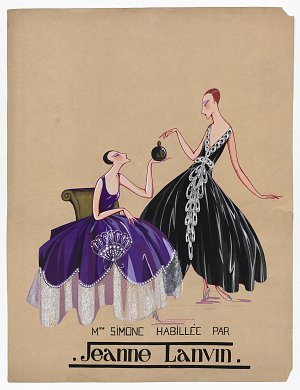

Marguerite Porracchia, Mme Simone dressed by Jeanne Lanvin 1920-1922

Donation by Bruno Gaudensi and Sandra Nahum, 2013

© Marguerite Porracchia

The Second Empire’s passion for the 18th century, epitomized by the influential Goncourt brothers (hence “G” standing for “Goût Goncourt”) is illustrated by the works of Carle Van Loo, François Boucher and Jean Honoré Fragonard. The museum’s collection of furniture drawings (M for Mobilier) displays studies for cabinets by André Charles Boulle alongside Joe Columbo’s Tube Chair and works by Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann and Jean Royère. Jewelry and fashion find their most charming expression in the “S for Seduction” section, with precious jewelry ensembles by René Lalique and Alphons Mucha, and recently identified sketches of dresses by Victor Lhuer for Paul Poiret, shown alongside the couturier’s Mosaïque dress (c.1910). A collection of drawings by Marguerite Porracchia, who illustrated Jeanne Lanvin’s designs, is shown here to the public for the first time. Lastly, the exhibition celebrates the splendors of the French capital in V for Vie Parisienne, brilliantly depicted by Jules Chéret’s drawings for Les Coulisses de l’Opéra au musée Grévin or Léon Bakst’s Décor pour Le ballet de Cléopâtre.

Robert Mallet-Stevens, Information and Tourism Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, Paris, 1925

© Les Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Resolutely cross-disciplinary in its approach, the exhibition showcases projects for gardens, sculptures, paintings, objects, silverware and wallpaper by both major and minor masters. It also affords the Museum the opportunity of displaying recent discoveries. Among these exhibits, scale models for the décors of the French Embassy Pavilion conceived for the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels of 1925, shown for the first time to the public. The most spectacular are, without a doubt, Albert Besnard’s lifesize pastel, Study for a Horse (1883) and Jean Souverbie’s rediscovered model for the monumental staircase of the Théâtre national de Chaillot (1937), both restored for the exhibition.

140 years after the first major exhibition dedicated to designs for decoration and ornamentation by past masters shown by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs at the Palais de l’Industrie in 1880, “Drawings Without Reserves” is an invitation to discover the incredible diversity of a unique, evergrowing collection. It aims to shed light on its history and contours, but also to envision the future of a collection initially created to supply models for artists, which has come to illustrate the full scope of creation of the past six centuries.