Court belt, India or Iran, 17th century

Silk, silver thread

Musée du Louvre, Paris, département des Arts

de l’Islam

© 2007 musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault

Founded in 1847 by Louis-François Cartier,

the House of Cartier initially specialised

in selling jewellery and works of art.

His son, Alfred, took over the management

of the business in 1874, and his eldest son,

Louis, later joined him in 1898. By that time,

Cartier was designing its own jewellery,

while continuing to resell antique pieces.

At the beginning of the 20th century,

Louis Cartier sought new inspiration.

At the time Paris was the epicentre of the

Islamic art trade and it was undoubtedly

through major exhibitions organised at the

Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1903

and then in Munich in 1910, that Louis

enthusiastically discovered these new

shapes which were gradually spreading

throughout French society.

The exhibition is organised as a themed

chronological tour divided into two parts,

the first of which explores the origins

of this interest in Islamic art and

architecture through the cultural backdrop

of Paris at the beginning of the 20th

century and reviews the creative context

among designers and studios as they

searched for sources of inspiration.

The second part illustrates the lexicon

of forms inspired by Islamic art, from the

start of the 20th century to the present day.

Tiara, Cartier London, 1936

Platinum, diamonds, turquoise. Vincent Wulveryck. Cartier Collection

© Cartier

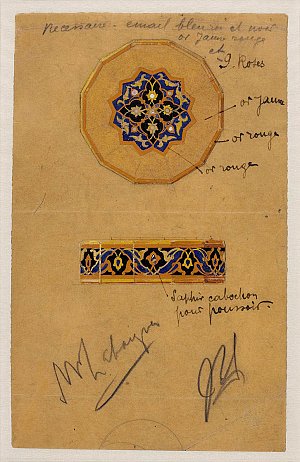

Proposal for a powder box, Cartier Paris, circa 1920

Graphite pencil, Indian

ink and gouache

on tracing paper.

Cartier Paris Archives

© Cartier

From the outset, visitors find themselves

immersed in these shapes and motifs

with three of Cartier’s iconic creations set

against masterpieces of Islamic art. Along

the North Gallery, you are invited, room

after room, to explore the creative process

and the initial sources of inspiration

in jewellery design. The books in Louis

Cartier’s library and his collection of Islamic

art were made available as resources for

designers. Louis’ personal collection,

reconstructed thanks to the archives of the

House of Cartier, is represented here

through several masterpieces reunited

for the first time since the dispersion

of his collection. Charles Jacqueau was

an important as well as brilliant member

of Cartier’s team of designers. A selection

of his design drawings is presented here

thanks to an exceptional loan from the

Petit Palais, Fine Arts Museum of Paris.

Facing panel, Iran Late 14th - 15th century

Ceramic mosaic

Musée du Louvre, Paris

département des Arts

de l’Islam, on loan from

the Musée des Arts

Décoratifs, Paris

© 2010 musée du Louvre / Raphaël Chipault

The exhibition continues by exploring

Jacques Cartier’s travels, including to India

in 1911, where he met with Maharajahs

of the subcontinent. The trading

of gemstones and pearls offered

Jacques Cartier a way into this country.

It enabled him to build relationships

with Maharajahs all the while collecting

antique and contemporary jewellery, which

he would either resell unchanged, use

as inspiration, or dismantle for integration

into new designs.

These different sources of inspiration,

and the Oriental jewellery that enriched

the House of Cartier’s collections helped

to redefine shapes as well as craftsmanship

techniques. The head ornaments,

tassels, bazubands (an elongated

bracelet worn on the upper arm) came

in a wide range of shapes, colours and

materials to suit the fashions of the time.

The flexibility of Indian jewellery led

to technical innovation, new settings, and

different methods of assembling pieces.

Incorporating different parts of jewellery,

fragments of Islamic works of art referred

to as ‘apprêts,’ and the use of Oriental

textiles to create bags and accessories,

was also a hallmark of the House of Cartier

in the early 20th century.

Pyxis, Sicily 15th century

Ivory (elephant), copper

alloy.

Exhibited at the Islamic

Arts exhibition,

Paris Musée des Arts

Décoratifs, 1903. Musée du Louvre, Paris

département des Arts

de l’Islam

© 2015 musée du Louvre / Chipault - Soligny

The second part of the exhibition, in the

South Gallery, is dedicated to the lexicon

of forms inspired by Islamic art, particularly

thanks to the collections belonging to

the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the

Musée du Louvre. Most of these works

were displayed at the first-ever exhibitions

devoted to Islamic art. They certainly would

have been seen by the Cartier designers or

known to them thanks to the publications

kept in Louis Cartier’s library.

Although famed for its ‘garland style’

jewellery, from 1904 onwards, Cartier

began developing pieces inspired

by the geometric patterns of Islamic art

found in books about ornamentation

and architecture. Enamelled brick

decorations from Central Asia and

stepped merlons, amongst others, form

the basis of a precursory repertoire later

described as ‘Art Deco’ - in reference

to the ‘Exposition internationale des arts

décoratifs et industriels modernes’ in Paris

in 1925, bringing Cartier into the modern

world very early on.

Cartier’s production under the artistic

direction of Louis Cartier is notable for

the inspiration he took from the Persian

world as well as the art of the book.

The patterns which decorate bindings –

the central medallion surrounded

by fleurons and corner pieces – were

sometimes reproduced exactly, but more

often pulled apart and recreated to form

a pattern whose source is indiscernible

to the untrained eye. This is the case with

mandorlas, palmettes, foliage, sequins,

scrolls, scales, etc. Louis innovated

with bold combinations of colours

and materials, combining lapis lazuli

and turquoise, matching the green

of jade or emerald with the blue of lapis

lazuli or sapphire to create his famous

‘peacock pattern.’Cartier’s production under the artistic

direction of Louis Cartier is notable for

the inspiration he took from the Persian

world as well as the art of the book.

The patterns which decorate bindings –

the central medallion surrounded

by fleurons and corner pieces – were

sometimes reproduced exactly, but more

often pulled apart and recreated to form

a pattern whose source is indiscernible

to the untrained eye. This is the case with

mandorlas, palmettes, foliage, sequins,

scrolls, scales, etc. Louis innovated

with bold combinations of colours

and materials, combining lapis lazuli

and turquoise, matching the green

of jade or emerald with the blue of lapis

lazuli or sapphire to create his famous

‘peacock pattern.’

Bib necklace, Cartier Paris, commissioned in 1947

Gold, platinum,

diamonds, amethysts,

turquoise.

Commissioned by the

Duke of Windsor for the

Duchess of Windsor. Nils Herrmann. Cartier Collection

© Cartier

In the 1930s, under the artistic direction

of Jeanne Toussaint, Cartier’s style

gave way to new shapes and colour

combinations inspired mainly by India.

Tutti Frutti pieces, sautoirs, and voluminous

jewellery characterised Cartier’s highly

recognisable style and its creations of the

second half of the 20th century.

The tour of the exhibition ends in the

Central Hall with digital devices created

by Elizabeth Diller’s teams from the DS+R

studio, bringing another dimension to the

jewellery.

The patterns and shapes from Islamic

art and architecture, sometimes easily

identifiable, at other times broken down

and redesigned to make their source

untraceable, became an integral part

of the stylistic vocabulary of the designers.

Today, they still form a part of the

Cartier repertoire, as illustrated by the

contemporary jewels which complete

the exhibition.

Head ornament, Cartier New York, circa 1924

Platinum, gold, diamonds,

feathers. Marian Gérard. Cartier Collection

© Cartier

For the first time, light will be shined

on the design process of one of the

world’s most renowned jewellers, the

House of Cartier. The tremendously rich

archives, many design drawings, and

photographic collections have all made

it possible to trace the original source

of many Cartier designs, allowing us

to understand the huge impact that the

discovery of Islamic art had on the House

of Cartier at the start of the 20th century.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs paved the

way for this specific research with the

exhibition ‘Purs décors ? Arts de l’islam,

regards du XIXe siècle’ in 2007, and loaned

its substantial collections of Islamic art

to those of the Musée du Louvre to form

the singular Department of Islamic Arts,

inaugurated in 2012. Today, this research

and understanding of jewellery has

intensified thanks to the study of Cartier’s

design history.